| Date | Aircraft | Route of Flight | Time (hrs) | Total (hrs) |

| 23 Nov 2008 | N21481 | 5G0 (Le Roy, NY) - DSV (Dansville, NY) - ROC (Rochester, NY) - 5G0 | 1.2 | 674.6 |

A couple of times a year, I descend toward the heart of Class Charlie airspace surrounding the Greater Rochester International Airport for some practice with the control tower there. I do this to keep my ear proficient because I do not routinely fly into towered airports. As a student trained at a non-towered field, my early interactions with air traffic control (ATC) were awkward at best (e.g., “Mishaps at Muskegon”). Learning from that experience, I worked to improve my comfort level with ATC once I became an aircraft owner. In my opinion, it pays to exercise that ATC fluency from time to time. While climbing away from a lunch stop at the Dansville airport, I decided that I was due for some practice and made an initial call to Rochester approach to get their attention.

“Warrior 21481, go ahead,” responded the approach controller.

”Warrior 21481 is 20 miles south at three thousand, inbound for touch and goes with echo.” For the uninitiated, a “touch and go” is a landing with a short roll followed by an immediate departure. I had no desire to drive around the surface of Greater Rochester International; the point was to fly in and work with the tower.

"Warrior 481, squawk 0333 and ident.” I dialed the code into my transponder and pressed the "ident" button that would momentarily brighten my aircraft on the controller's screen. At the moment, Rochester was moderately busy and the approach controller was working a combination of airliners, private jets, and single engine general aviation aircraft like mine.

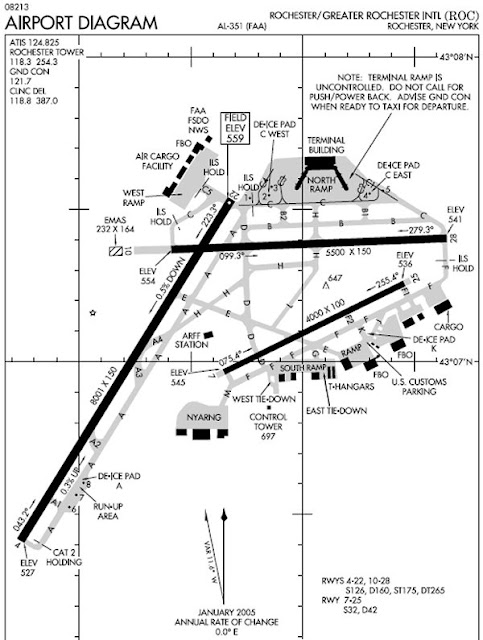

“Warrior 481, radar contact one eight miles south of Rochester. Turn right heading 040, vector for runway two five.” Runway 25 is Rochester’s dedicated general aviation runway. Instrument traffic, including everything from single engine piston aircraft to commercial airliners, was using runway 22 that day.

I turned on course and listened to the chatter between ATC and other aircraft converging on the airport. Once I was within ten miles of Rochester, I could clearly see the airport as a snow-covered field. Due to their orientation, the runways were invisible from my position, but I could see the control tower standing tall on the south edge of the field. Shortly thereafter, Rochester approach called again.

“Warrior 481, turn left heading 020, vector for left base runway two five. Let me know when you have the field in sight.”

“020, Warrior 481,” I transmitted back to approach while banking to the new heading. “And I have the field in sight.”

“Warrior 481, contact tower on 118.3 and have a good day.”

I switched to the other radio, already set for Rochester’s tower frequency. Protocol is to “check in” on the new frequency. In this instance, simply calling with my tail number should have been adequate. The approach controller should have communicated my intentions to the tower controller already. I expected the tower to respond with a clarifying question or a directive to continue on left base leg for runway 25.

I waited for a lull on the tower frequency before checking in. “Rochester tower, Warrior 21481.”

No response. I waited for the tower to finish communicating with a couple of other aircraft and tried again. “Rochester tower, Warrior 21481.”

“Warrior 481, go ahead.” Go ahead? It was as though the tower controller thought I was making a new request rather than checking in. This did not fit the communication paradigm in my head. Not knowing what else to say, I decided to remind the tower where I was and what I was doing. “Warrior 481 is on extended left base, runway two five.”

“Warrior 481, clear to land runway two five.” I was at least eight miles out. I acknowledged the landing clearance, but something seemed wrong. Then I realized that the tower should have cleared me for a touch and go, not a landing. Did the tower controller not have information from the approach controller or had he simply made a slip of the tongue?

Rather than wonder, I called again. “Rochester tower, Warrior 481 verifying clear for touch and go, two five.”

The controller stumbled a bit on the radio. “Ah…negative, Warrior 481, you are clear to land two five.”

“Clear to land, two five, Warrior 481.” I began to ponder what I would do once earthbound at Rochester. Taxiing around the airport was not part of the plan. Do I even have a taxiway diagram with me? I didn't know. Poor planning on my part, perhaps, but a diagram would not have been necessary for merely rubbing my tires on one of Rochester's runways a few times.

These thoughts were interrupted by the tower calling back. “Warrior 481, do you want a touch and go?”

“Affirmative, Warrior 481,” I answered.

“Warrior 481, you are clear to land runway two five. Hold on the runway.” I repeated the clearance, half wondering if I heard it correctly. When the controller did not correct me, I realized that it was for real. He wanted me to land on runway 25 and just sit there, counter to every instinct I would have telling me to clear the runway as soon as possible.

On final approach, I took stock of the situation. Another Cherokee taxied to the departure end of runway 25 and behind it was a Cessna 400 (nee Columbia) . Across the airport, an airliner in Delta livery was plodding along a taxiway en route to the commercial terminal. I could also see a Cessna across the airport on final approach for runway 22 with full flaps deployed. From my time on the approach frequency, I knew that several other jet aircraft were inbound, but none had switched to the tower frequency yet.

At that moment, the airborne Cessna called the tower. He had obviously listened to my exchange with the tower and now doubted his own clearance. “Ah, Rochester tower, Cessna 123, am I clear for a touch and go?”

Sounding flustered, the tower controller replied, “uh, negative Cessna 123. You are clear to land two two. Did you want a touch and go?” Clearly, there was a communication breakdown between the approach and tower controllers at Rochester that afternoon.

I floated low over the runway numbers and as the stall warning horn began to sound, I rolled the Warrior’s wheels onto the runway in one of the softest landings I had made in a long time. I pulled the yoke back to my chest and waited for the nosegear to contact the runway before pressing the brakes. I brought the Warrior to a full stop in the middle of the runway, about one third of the way down.

From my location on runway 25, I could look to my left and see the control tower. Don’t forget about me, I thought at the tinted windows surrounding the tower cab. I sat there, idling, feeling very vulnerable. I have read a few accident reports involving ATC mistakenly clearing aircraft to land or depart a runway already occupied by another airplane. For this reason, it is generally good practice to exit a runway as soon as possible after landing. This is particularly true at the non-towered airports I usually frequent.

From the activity on frequency, it was obvious that the controller was waiting for an opportune lull in jet traffic on runway 22 that would allow me to launch without posing a conflict. I do not know how long I waited in the middle of that runway, intently listening for the controller to slip up and clear someone to land or depart runway 25 while I still occupied it. My hand rested on the throttle and my eyes focused on a nearby taxiway – my closest escape if any mistakes were made.

My discomfort slowed the progress of time. Eventually, like a golden sunbeam puncturing an iron gray overcast, I finally heard the tower controller utter my tail number. “Warrior 481, cleared to depart runway two five, make left traffic.” I think I actually heard angels singing in the background.

As I advanced the throttle, I could feel that my shoulders had tightened during the tense wait. I was climbing skyward, freed from a vulnerable position on the runway, and could feel the knots in my shoulders loosening. From the traffic pattern, I watched the Cherokee that had been holding behind me depart runway 25. I made three touch and go landings on runway 25 that afternoon and my airmanship was excellent; patterns were well-flown and landings were greasers. Just prior to the third landing, I told the tower that I was ready to return home to Le Roy.

“Warrior 481, turn right on course, Le Roy.”

Turn right? I glanced at the GPS and verified a suspicion that flying runway heading would take me directly home; no turns required. Because he did not dictate a heading, I acknowledged “on course, Le Roy, Warrior 481” and continued on runway heading. Within the next couple of minutes I was switched back to the departure frequency, given a new transponder code, and shown the way out of Class Charlie airspace by the same controller that had guided me in. Upon reaching Le Roy, the departure controller wished me a good day, advised that no traffic was observed in the vicinity of the airport, and released me from the system.

I brought the Warrior back to earth on a runway covered with an inch of snow. I waited for the bump that signified contact of the main gear with the pavement, but it never came. One moment I was floating over the runway and the next, I was rolling. I decided that I liked having an inch of snow on the runway. It was like landing on a pillow.

As always, the exercise of flying into Rochester was time well spent. It certainly underscored the necessity to pay close attention (this goes without saying) and double check confusing clearances rather than trying to divine what the controller may or may not have meant. But more importantly, the episode served as a reminder that the control tower is not Mount Olympus and its inhabitants are not deities, but human beings that can make mistakes. This is not an indictment of Rochester ATC; the folks at Rochester work hard and, in my admittedly limited experience, have always been extremely helpful and professional. The point is that while both pilots and controllers are capable of mistakes; the system still works well as long as we have patience and watch out for one another.